Listeners:

Top listeners:

-

play_arrow

KTSW 89.9

By Ché Salgado

Music Journalist

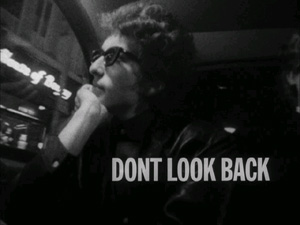

This year marked the 50th anniversary of D.A. Pennebaker’s landmark documentary, Dont Look Back, released in 1967, which follows a young Bob Dylan–quickly ascending to the peak of his fame–on his spring 1965 tour of England. Throughout the documentary there are several moments which offer, more than anything else at the time, a window into the artist (that is, the artist as a concept) as a person rather than an entertainer, as someone with insecurities, convictions, desires, and most of all, autonomy, rather than somebody who is simply working. For capturing one of the most iconic artists of the ’60s playing his role in the challenging of traditional norms in youth-driven pop culture, this documentary is indispensable.

To completely understand Dont Look Back, it’s important to understand not only the canon of Dylan himself but also how 1965 fits into the canon of pop music. Author Michael Gray, who’s written extensively about pop music, has argued that our vision of “The Sixties” really began to take hold in 1965. It isn’t hard to see how in this year pop music took a more creative turn, taking a step away from its origins as a consumer good and a step toward the collection of personal artistic statements we know it as today. There are the well-trod examples: The Beatles’ Rubber Soul, their first album of all original songs which influenced the likes of Brian Wilson, who even in 1965 was beginning to make craft more experimental music, like “Help Me, Rhonda” (those false fade-outs!) which presaged something greater.

But this shift wasn’t only evident in the musical heavyweights and it wasn’t only about the music, but image too. Take two (now) relatively obscure (but excellent) girl groups of the era: The Angels and The Shangri-Las. On record they’re comparable no matter what year. But take these two television appearances recorded just two years apart: The Angels doing “My Boyfriend’s Back” on CBS’ “Ed Sullivan Show” in 1963 and The Shangri-Las doing “Out in the Streets” on ABC’s “Shindig!” In 1965. The differences are so stark, they’re skyscrapers. In the former clip you can see a prime example of how the first few years of the ’60s resemble something we’d more readily file under our mental picture of the ’50s. The latter clip is nothing like it. Everything is different: from the somber nature of the content to the way it’s presented. We get several moving shots of the group performing under lighting that constantly changes. Everything about it offers a more creative, edgier picture than a fixed camera angle and static lighting. Even the group’s performance itself, involving singing while performing choreographed movements helps send the message that you must know now if you hadn’t known it before: the pop landscape was changing in 1965.

And at the center of it all was a 23-year-old who was born in Duluth, and raised in Hibbing, Minnesota. Once described by Andy Warhol as “The Definitive Pop Star—possibly of all time—who was then fast gaining recognition on both sides of the Atlantic as the thinking man’s Elvis Presley”, Bob Dylan, born Robert Zimmerman, was already huge by the time 1965 rolled around. He as well as his music, was changing in a way that would shift the way we view pop music as a cultural force, and it was all caught on film.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” is the first thing you hear in Dont Look Back which is appropriate since it’s the first bit of new music Dylan fans had heard from him in almost a year. For the fans of folk Dylan, this new record was jarring. There’s a moment in Don’t Look Back, around the 22-minute mark, wherein Dylan has the following exchange with a fan:

Fan: “I don’t like any of the, um, ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues.’”

Dylan: “Oh, you’re that kind of- I understand right now.”

F: “It’s not you. It doesn’t sound like you at all.”

In this exchange we see the burgeoning divide between Dylan and his fans that would widen as 1965 turned to 1966 (Dylan would return to England in spring 1966 for an electric tour, which was met with heavy boos). To understand this, it’s vital to understand that folk music as an art form was more or less the polar opposite to pop music, and even to rock and roll (long hailed by snotty dudes as Music That Has Something To Say). These forms, to the folk fan, were empty. What was music if it didn’t have a message? And Dylan had a message, and then suddenly in the course of one single it was gone.

This was especially dramatic considering the single released before “Subterranean Homesick Blues” was “The Times They Are a-Changin’”. To go from prophesying “Come senators, congressmen/Please heed the call/Don’t stand in the doorway/Don’t block up the hall/For he that gets hurt/Will be he who has stalled/There’s a battle outside and it is ragin’/It’ll soon shake your windows and rattle your walls/For the times they are a-changin’”, to singing “Look out kid/Don’t matter what you did/Walk on your tiptoes/Don’t try “No-Doze”/Better stay away from those/That carry around a fire hose/Keep a clean nose/Watch the plain clothes/You don’t need a weatherman/To know which way the wind blows”? With so wide a divide between folk and pop and the weight and significance that folk fans placed on their preferred genre, and with the fact that Bob Dylan really was like a prophet to these people; one music writer put it like this: “It was like God turned away from everyone.”

Appropriately, when he returned in 1966 for his electric tour of new pop material, they called him “Judas”. Throughout Dont Look Back, instances like these, where the music of Dylan is made out to be something of a prophecy, where Dylan himself is made out to be the voice of his generation, occur again and again and in each instance Dylan either downplays the complexity of his own lyrics, or looks very uncomfortable. It begs the question: how different were folk and pop music really if, at the core, they both viciously denied the artist any sort of autonomy? What makes the booing folk fan different from pop villain Mike Love who called “Pet Sounds”, the Beach Boys’ pinnacle, a failure for the fact that it didn’t go gold upon release? After the conclusion of the tour documented in Dont Look Back, Dylan would go on to further alienate fans who’d looked to him as a folk luminary by going fully electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, releasing the electric smash hit “Like a Rolling Stone” which went to #2 on the charts, and, by August, he’d release Highway 61 Revisited, the album about which author Michael Gray was talking about when he argued that “The Sixties” began in 1965.

And so, for capturing Dylan in this transitional period of time for pop music, Dont Look Back is an important record about how one of the era’s greatest stars became a model for the modern pop-musician as something that isn’t inherently unintellectual, something that doesn’t have to adhere to anything other than their own artistic vision. And while Dont Look Back plays into Dylan mythmaking, just like this article does, it’s actually the best document we have that displays to us Dylan’s humanity. Sometimes we see a documentary about musicians, like Stop Making Sense, and it’s no fault of Jonathan Demme, that film’s director, or The Talking Heads, its subject, but they do come out of it all looking untouchable. (David Byrne dancing around a lamp in an oversized suit, like he’s from another planet.)

Dont Look Back is not a concert film. There are shots of the shows on the 1965 tour but they’re usually sandwiched between moments that give them a new context. For example, footage of Dylan’s show at the Great Albert Hall is followed by footage in which Dylan seems awestruck by what he’s just done. He’s not an auteur, he’s a kid. It’s candid moments like these which give the film the depth that a concert film couldn’t. Thanks to the fly-on-the-wall look at Bob Dylan and his entourage -which includes Joan Baez (folk star in her own right), Bob Neuwirth (tour manager and musician), Alan Price (a keyboardist who had just left his group, The Animals), and his manager, Albert Grossman- we get to see Bob Dylan be funny, annoyed, tired, sad, insecure, drunk, as well as incredibly mean. In this way, Dylan fleshes out his public persona as a person rather than a musician which we can just throw admiration onto.

Possibly the best scene in the film is one which deconstructs the image of a cool, cigarette smoking Dylan and instead presents him to us as a person who in a matter of moments experiences and displays a number of emotions. In the scene, Dylan yells at a room full of guests, telling them that, unless whoever had thrown a glass out of his hotel bathroom window onto a limo below takes responsibility, “you’re all gonna get the f**k out of here and never come back!” Dylan is angry, incendiary, and he’s too drunk to reasonably deal with the weight of his fame as it bears down on him as he’s held responsible for the actions of his guests by the hotel. He then expresses regret to the hotel manager, clearly embarrassed about the actions of his guests.

In so much of this documentary we see Dylan go on record with reporters as a sardonic figure, giving answers that are either jokes, or just wrong, though those aren’t mutually exclusive. In moments like these, like in this scene, we see a genuine Dylan not entirely comfortable with the weight of his fame and not entirely secure with himself as a writer, as we see when the scene progresses, and Dylan meets Donovan. It’s important to note that Donovan is like a spectre that hangs over Dylan and his entourage in this movie. He’s frequently mentioned mostly in a Dylan vs. Donovan context, as Donovan is on the rise, and Dylan’s just released a single that his fans don’t like.

In the encounter that follows we see Donovan and Dylan have what’s basically a song-off which offers Dylan the chance to validate his work not only to himself but to the whole room. We see director, D.A. Pennebaker, again employ a technique which he does often, sticking the camera on people’s faces. It’s consistently effective for tapping into the feeling of the room, but especially here. Look at Donovan as he watches Dylan perform “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” after his own “To Sing For You”, the YouTube comments agree, he knows he’s lost. And look at how smug Dylan looks as he performs to the room. He’s relieved, he’s happy, he’s won. What else could elicit something like this but deep personal doubts and insecurities about the validity of your work compared to others?

The film is so littered with instances like these, such as when Bob interrupts a backstage Alan Price performance to ask him why he left The Animals, a question that throws him, silences him, and allows Dylan to become the center of attention in the room. There’s a shot wherein Dylan just takes off his sunglasses and holds his head in his hands for a few seconds. To analyze every instance would be impossible, not to mention useless, since they all serve to say the same thing. And that is this: this was a time when the pop star was becoming someone more than a product, someone more than a two-dimensional persona to be sanitized and made appealing for the masses, as consumer products are. In 1965 when the notion of a pop star as an individual with as many insecurities and flaws as endearing qualities was forming, along with the idea that the music made by these pop stars was a vehicle through which they expressed themselves, Bob Dylan was at the center of it.

Unwittingly, by harnessing notions indelibly tied to him through his roots in folk music–notions of significance and meaning in the music as well as something vaguely, but acutely, anti-establishment–and bringing these concepts to the realm of mainstream pop music through his crossover success in 1965, he set the stage for the ’60s counterculture and all pop stars that would come after him. The concept of the creative but difficult pop genius was born in the ’60s and it’s what Dylan embodies in Dont Look Back. It’s an image of an artist at the peak of fame. He plays to sold out crowds, he narrowly escapes hordes of fans trying to touch him, and through it all he’s pursuing a vision of the future of his own art which he seems to be the only believer in. He does this while subverting and brushing up against the trappings of what it meant to be a pop star before films like Dont Look Back made it okay for a pop star to act like Bob Dylan acts.

That’s why this film is so indispensable in the canon of pop history: for capturing an icon at his most popular and most influential, D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary is arguably as important as even the music of its subject in proving that Bob Dylan was at the forefront of all these things that coalesced in 1965 to form the base of the modern pop star and change the relationship between music, money, and the public, forever.

Featured image via Don’t Look Back.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

1965 50th Anniversary Bob Dylan Che Salgado documentary Don't Look Back KTSW Music

Similar posts

This Blog is Propery of KTSW

Post comments (0)